(Photo: towbar)

Coparenting has been described as the relationship parents share in the business of raising children, and the quality of this relationship is linked to both child and parent outcomes.1,2 Children from higher quality parenting partnerships experience superior social and emotional development including enhanced skills in emotional regulation.3,4 It is also important to note that most mothers and fathers report that their parenting partnership – not service providers – is their main source of parenting support. It is therefore not surprising that parents in stronger parenting partnerships experience lower levels of parenting stress and higher levels of parenting self-efficacy (the belief their parenting will make a difference).4,5 It is therefore encouraging to know that the quality of parenting partnerships can be enhanced through intervention, and that associated improvements in the parenting relationship have been linked to lower parenting stress, enhanced perceptions of child behaviour, and reduced antecedents of family violence.1,3 However, interventions to improve parenting partnerships have not taken a substantial foothold in family practice.

A key factor that limits the application of parenting partnership interventions in mainstream practice is that many of them have been designed to be delivered to parenting couples.1,6 Many practitioners, however, report that it is difficult to get more than one parent to attend parenting interventions – with the exception of antenatal classes where it appears that many fathers attend to support their partner7 – and this low rate of participation is often due to the reluctance of fathers.8

When services have addressed identified barriers to engaging fathers, with the aim of attracting fathers to parenting related activities – such as running programs after hours, advertising directly to fathers, serving food, and focusing on specific aspects of the father-child relationship – father attendance and retention usually still remains low.8 When fathers do attend programs there are often high dropout rates.9 There are many possible reasons fathers do not engage with services including gendered parenting roles, mothers feeling more confident in dealing with family services, decisions about the best use of the fathers time, and decisions about the division of roles and responsibilities.10,11 This does not necessarily mean fathers are uninvolved in the lives of their children.

Rather than attempting to force fathers to engage with services, an alternative is to accept that many fathers are unlikely to directly engage with family service and to explore parenting partnership practices and programs.

This paper presents an Interactive Effects Model of Intervention in Family Services (IEMIFS) designed to demonstrate the interactive nature of family systems, key relationships that influence outcomes within most family systems, and the way that the processes that providers work through influence provider expectations and behaviours (Figure 1).

Before discussing the model it is important to note that although the parenting team in most families continues to comprise the biological mother and father, with almost 80% of Australian 15 year olds still living under the same roof as their biological parents, parenting partnerships come in many forms.12 Many single parents care for their children in close relationship with their own parents or with other adults who work with them to form a family’s parenting team.

Figure 1: An Interactive Effects Model of Intervention in Family Services (IEMIFS)

Figure 1: An Interactive Effects Model of Intervention in Family Services (IEMIFS)

Implications for Practice

The IEMIFS illustrates that…

- The parenting partnership is ever-present – even when both parents are not.

- Interactions with any member of the family are likely to have a flow on effect through all of these key family relationships.

- Practitioners are influenced by both the interaction and the process that they employ.

The top triangle of IEMIFS (Mum-Dad-Child) describes interactions that occur within the family.13,14 It demonstrates that couples who share the parenting of a child share a rich and complex environment in which there are influential relationships between each parent and the child and a third interaction between the child and the parenting partnership. The model also shows that the parenting partnership is different to, but linked to, the parents’ romantic relationship (illustrated by the dotted line between the parents). It is important to note that influence in relationships is always two-way and therefore factors such as the temperament of either the child, parents, or both will influence how mothering, fathering, and the parenting partnership functions.

The bottom half of the model describes interactions that occur between families, service providers, and the processes that providers employ. This section of the model illustrates how family workers, and other service providers, work through processes in their interactions with the family and that the processes and the providers are influenced by these experiences. With the majority of interactions occurring down the left hand side of the EIMIFS, with mothers and/or children, providers learn to expect and plan for this mode of interaction while getting relatively little experience in working with either parenting partnerships or fathers. This continues to be the case in contemporary society where fathers are spending more time caring for their children either in partnership or on their own.

For many families, the mother will be the parent that interacts with family services. Service providers can improve their practice by recognising that, in many families, both parents will support this division of labour. In some families one or both parents might want the father to be more involved in these interactions, but other issues (e.g., highly feminised workforces in health and education where mothers are more likely to feel both capable and comfortable, appointment times that clash with paid work, and the gendered expectations of employers, service providers, and the parents themselves) get in the way.

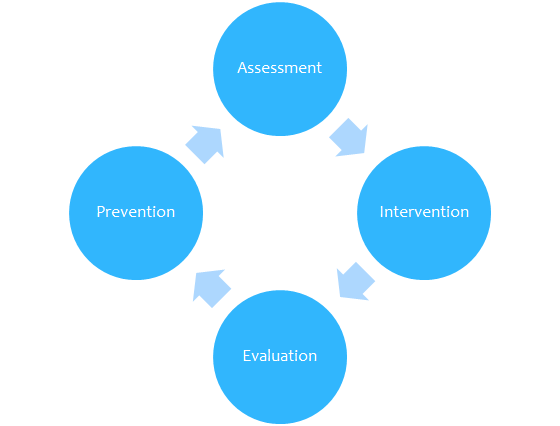

While services need to be able to engage directly with fathers, services also need to consider how they can positively influence both parenting partners and partnerships when only one parent attends appointments or programs. Figure 2 illustrates four opportunities that occur in the relationship that parents share with service provision. The remaining sections of this paper will briefly describe some tools and processes that have been developed to help service providers engage with parenting partnerships at each of these opportunities.

Figure 2: Four Opportunities to Engage with Parenting Partnerships

Figure 2: Four Opportunities to Engage with Parenting Partnerships

Assessment

The assessment phase presents an opportunity to activate processes that engage both parents in discussing and reporting both individual and collective expectations. The Family Assessment Kit is one example of how the assessment phase can be taken home and explored by all members of the parenting partnership in their own time, in a comfortable space, without the influence of providers who may inadvertently influence the outcome.

The kit contains three sets of identical cards that parents can sort individually and/or collectively. The aim is for parents to identify their highest areas of need and then compare these to those of their partner. Parents can then return the sorted kit to the service where providers can use a scoring sheet to help them understand the level of agreement that exists between parents, their individual and collective areas of highest need, and develop a more holistic understanding of factors that should be taken into account in planning intervention. However this process also creates an opportunity to engage with the broader family and potentially enhance the quality of family relationships. Many parents have now reported that this process was both enjoyable and helpful with one father of a child with autism reporting that it was a “brilliant” experience “for the first time ever, sitting down and having a real conversation about what we want for our child and our family”. For more information go to www.familiesconnectingthedots.com.au

Intervention

The Family Action Centre has also constructed a simple tool that helps practitioners to include all members of the parenting partnership in the development of intervention plans. Practitioners can use this tool to explore four simple questions about each of the adults (parents, carers, grandparents, etc.) who play a role in the child’s life and could therefore influence the outcome of any intervention. The questions are as follows:

- How do you imagine the role of …… (name of person in the partnering team) in working towards your goals for your child?

- How will this be different to what …… (name of person in the partnering team) normally does?

- What skills/abilities does …… (name of person in the partnering team) have that will help?

- How will your/his/her relationship with [child/family] help to achieve the goals for your child?

Our experience in using this simple tool is that it can reveal opportunities that could have been overlooked in the planning of intervention because the roles of these other players often go unexplored. For example in one family it became apparent that wrestling that occurred with a child’s father was an opportunity to work on particular motor skills and in another family that phone conversations with Grandma were an opportunity to encourage a young boy, who preferred to use body language, to develop verbal language skills. In one case this tool generated a discussion that contributed to a teenager returning to school after almost 2 years of school refusal.

Evaluation

Although we have not developed specific tools for this step the information gained in the assessment process along with information gathered during systemic intervention planning could also play a role in evaluation.

Prevention

A parenting partnerships program, developed through the Family Action Centre, invites only one member of the partnership to attend but aims to engage the other parent through take home activities and through their mobile phones. Recent experience (SMS4dads) tells us that fathers are prepared to receive relationship based messages and linked information on their mobile phone (See www.sms4dads.com). More expertise is being developed in shaping messages such as these, in developing and finding appropriate links, and in understanding how these experiences will influence behaviour change. In the meantime it is important to know that fathers are reporting that SMS4dads is helping them to feel less isolated during the transition to parenting, to build stronger relationships with their partner, and to develop early and stronger relationships with their children.

Conclusion

While there is wide acceptance of the importance of father inclusive practice, many family services continue to struggle to engage fathers. Even where services demonstrate best practice in working with fathers, their main contact is often still with mothers. This does not mean that fathers are uninvolved or disinterested, nor does it mean that services should miss opportunities created during interactions with any member of the family to engage with and consider the needs, expectations, and potential contributions of other parenting partners.

As well as ensuring that services are father friendly, family workers can adopt an approach that facilitates, encourages and supports parenting partnerships. Such an approach recognises the complex interactions that occur in families and the important roles fathers play in raising children. At a broader level this approach provides opportunities to consider how everyone in the parenting team can contribute to achieving positive outcomes for children.

The above paper was written by Chris May, with some input from me, from the Family Action Centre, University of Newcastle as part of a project supporting nine rural and regional family services to implement evidence-based programs and practice. The project was funded by the Department funded by the Department of Social Services through the Children and Families Expert Panel. You can see other posts relating to this work at https://sustainingcommunity.wordpress.com/resources-for-students/expert-panel-caps/.

If you liked this post please follow my blog (top right-hand corner of the blog), and you might like to look at:

- 36 ideas for helping to engage fathers

- Engaging fathers: An overview of evidence-based practice

- Being a father

- Engaging Aboriginal fathers

- 9 principles for supporting families and communities

- Playgroups as a foundation for working with hard to reach families

References

- Feinberg, M. E., (2003). The Internal Structure and Ecological Context of Coparenting: a Framework for Research and Intervention. Parenting: Science and Practice, 3(2), 95-131.

- McHale, J. P., & Lindahl, K. M. (2011). What is Coparenting?. In, J. P. McHale & K. M. Lindahl, (Eds.), Coparenting: A conceptual and Clinical Examination of Family Systems, (pp. 3-14). Washington DC: American Psychological Association.

- Majdandzic, M., de Vente, W., Feinberg, M., Aktar, E., Bogels, S. (2012) Bidirectional Associations Between Coparenting Relations and Family Member Anxiety. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 15, 28-42

- Teubert, D., & Pinquart, M. (2010). The Association between Coparenting and Child Adjustment: A Meta-Analysis. Parenting: Science and Practice. 10, 286-307.

- Feinberg, M. E., Jones, D.E., Kan, M. L., & Goslin, M. C. (2010). Effects of Family Foundations on Parents and Children: 3.5 Years After Baseline. Journal of Family Psychology, 24(5), 532-542. doi: 10.1037/a0020837

- Doss, B. D., Cicila, L. N., Morrison, K. R., Hsueh, A. C., & Carhart, K. (2014). A randomized controlled trial of brief coparenting and relationship interventions during the transition to parenthood. Journal of Family Psychology, 28 (4), 483-494.

- May, C., & Fletcher, R. (2013). Preparing fathers for the transition to parenthood: recommendations for the content of antenatal education. Midwifery. 29, 474-478.

- Fletcher, R., May, C., St George., Stoker, L., & Oshan, M. (2014) Engaging fathers: Evidence review. Canberra: Australian Research Alliance for Children and Youth (ARACY). Available from http://www.aracy.org.au/publications-resources/area?command=record&id=197&cid=6

- Unpublished data – Presented at University of Newcastle (2016) from Child Behaviour Research Clinic, Sydney University.

- Burgess, A. (2009). Fathers and Parenting Interventions: What works? Preliminary research findings and their application. Retrieved October 8, 2014, from http://www.fatherhoodinstitute.org.

- Crabb A. The Wife Drought. Sydney, Random House Australia, 2015.

- Baxter, J., Gray, M., Hayes, A. (2010). The Best Start: supporting happy, healthy childhoods, Available from https://aifs.gov.au/publications/best-start

Great work! As a counselor specialising in separated dads, I use a similar model called “The Sacred Relationships Model”, especially useful to show dads how their broken Romantic relationship is separate to their parental relationship. Men tend to see one as dependent on the other – and may give up on parenting when the romantic r/ship dies; which the annoys the Family Court -who they then blame for poor outcomes. They change when shown the model, so I think you are on the right path with this proposal. I am pleased to see that you are pushing against the “Deficit Male Model” in this piece. Men do try to support their child’s mother – often by stepping out of the way, but that is often interpreted as disinterest. Proof is that we do go to Ante Natal classes! But many other sessions are clearly so female aimed, that dads do not feel welcome, except as a background attendee. So they don’t go again, once they know the socially declared ‘real’ parent is OK there. I used to give a male session to the male partners of women with PND. I was given just 20 minutes with them, once, in 7 weeks. We were always late to rejoin the women; – they wanted much more. They wanted to help, but were not considered to be any use, despite that all the family suffered. So we just withdraw into the background (out of the way) and get labelled as disinterested.

Neill Hahn (T/as Private Concerns, formerly with SeparatedDadsWA.)

LikeLiked by 1 person

Reads like it was written by someone with no children!!!

LikeLike

Interesting, what makes you say that? We certainly both have children and are both active fathers! I can’t see anything that suggests we don’t have children.

LikeLike